How a business coach can help you unlock your full potential

May 19, 2023

A family tragedy led this attorney to start his own firm. Now it’s scaling up.

June 1, 2023By Verne Harnish

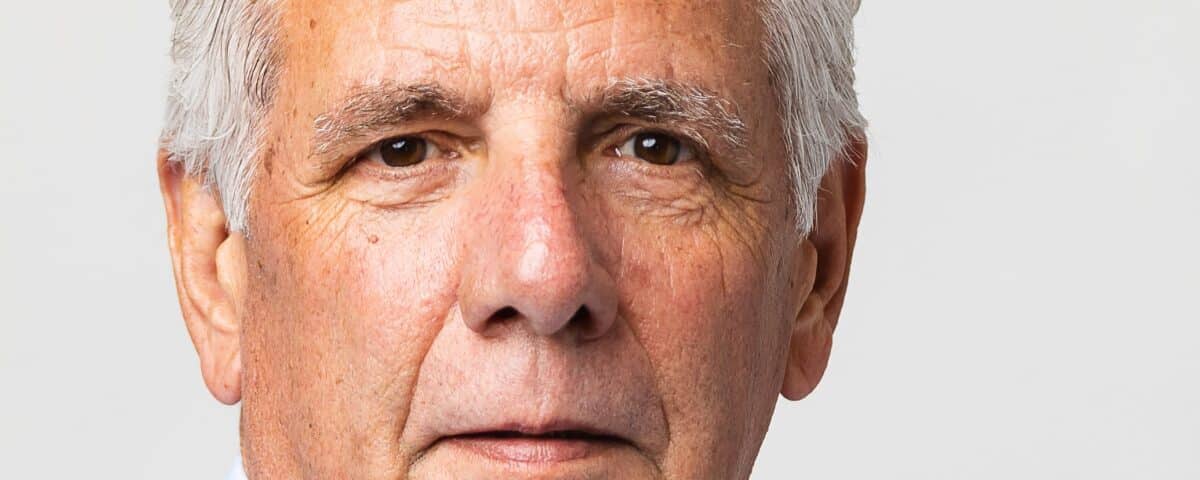

When Jim Sobeck acquired New South Construction Supply in 2001 from the original founders, the company was bringing in about $10 million a year in annual revenue. By the time he exited the now 41-year-old company for an undisclosed amount in March 2023, it reached $100 million in annual revenue and had about 135 employees.

Sobeck sold the construction products distributor–which sells concrete, masonry and waterproofing products at nine locations across the South to contractors–to Colony Hardware Corp., a distributor of construction materials based in Orange, Ct.

Making debt work for the business

So how did he position himself for his exit? His success goes back to the early days of the business, based in Greenville, S.C.

Sobeck initially used debt to buy New South Construction Supply, He and investors contributed $800,000 in equity, financing the balance with $1 million of sub debt, a $2 million seller loan, and the balance in bank debt. “You couldn’t have that kind of leverage today because of regulatory crackdowns,” he says. “We had to grow slowly. We couldn’t afford failure.”

But having a heavily leveraged business forced him to be a better operator. To position the business to scale up, Sobeck applied the ideas in Mastering the Rockefeller Habits, which he received at a meeting of Young Presidents’ Organization (YPO) in 1995. That meant holding Daily Huddles, monthly planning sessions, bi-annual management retreats, and annual meetings where the entire company and spouses/partners were invited to an annual coastal retreat to celebrate the year just ended and plan for the new one. The company also emphasized Cash, being careful not to extend too much credit to customers and keeping a close eye on inventory turns. By 2007, New South Construction Supply had grown slowly and steadily to $25 million in annual revenue.

Surviving a recession

Then the Great Recession hit, dealing a heavy blow to the housing market—and his industry. Sales dipped from $25 million to $13 million. “The bank put us in workout—that’s where bad kids go,” he jokes. “They put us on a very short leash.”

To keep the company afloat, Sobeck laid off 45% of the workforce, reduced his own pay by 35% for three years and cut everyone else’s salaries by 10%. “In a perverse way I really like recessions,” he says. “They force you to do things you don’t do in good times–take a hard look at people and costs.”

Embracing slow and steady growth

After the company emerged from its slump in 2010, it returned to its growth trajectory. To take it to the next level in revenue, he began hiring internal talent, such as a full-time IT team and a full-time HR manager. The company also branched out from light construction into new markets, such as residential, road and bridge, industrial, and restoration and repair.

“One of my mentors had told me go for the slow nickel not the fast dollar,” he says. “I pretty much had to do that and grow slowly and profitably, due to all the debt.”

It was after attending a recent YPO construction industry networking event in Chicago on preparing for the next recession that he began looking into getting rid of his personal guarantee for the company’s debt. The speaker suggested putting together a banking memorandum and sending it to every bank he knew to ask to remove the personal guarantees. Although his son—then the company’s CFO—doubted it was possible to get the banks to say yes, the company sent out the memorandum to 13 banks, and two did make an offer.

Having two potential partners put him in a position to negotiate. He asked the banker who ultimately backed him why she went to bat for his company later. She told him that she had no unanswered questions after watching a slide deck presentation he put together to document how the business survived the recession. Beyond that, both Sobeck and the business had built perfect credit scores.

“We not only got the personal guarantee removed from the revolving line of credit, but they also lowered our interest rate,” he says. “You get lucky at times with banks if they have excess cash they have to put to work, and it’s like finding someone who’s hungry when you have food. Even if they don’t necessarily love the food, if they’re hungry enough, they’ll eat it to survive.”

Building a better company

Sobeck also sought input from his team on how to make the business stronger at a company retreat. Taking their advice, he and his leadership team created a hardship fund to help employees with unforeseen financial challenges, began offering paid parental leave and started covering 100% of healthcare premiums for employees. That helped them attract top talent as they scaled. “We shared the wealth, and that became a virtuous circle,” he says.

When Sobeck got a call from a company scouting for acquisitions for a private equity group based in Boston, he was asked if he would be willing to talk with a platform company that was acquiring companies like his. He did so, and got an offer when he was vacationing in Italy with his wife. He appointed a committee of three board members to negotiate on his behalf. “Whenever you have somebody you can defer to, it gives you more time to think,” he says.

After four and a half months of negotiation, the deal closed. He took a significant amount of the proceeds in rollover stock, giving him a vested interest in the company’s continued success–and an incentive to offer advice when necessary, even though he is not on its board. Sobeck also sold off four warehouses he owned with partners.

Along the way, he wrote and published a book called The Real Business 101: Lessons From the Trenches in 2013. A publisher from China approached him with a big advance and generous royalty deal on a translated edition.

Now semi-retired, Sobeck is currently making investments in private equity funds and managing his real estate interests. He also has the luxury of time to spend traveling. He and his wife have visited 57 countries and aim to get to 100. He also works out at the gym daily, is writing his second book and reads avidly to keep his knowledge fresh. “I’m a lifelong learner,” he says. As I’ve always said, leaders are readers, and that’s making this new chapter of his life just as engaging as the first one.