Million Dollar Women; More Talking to Crazy; 100 Best for Women; Oct 16 Webinar

October 8, 2015

5 Ways To Avoid Commoditization

October 14, 2015Are ‘Plonkers’ Crushing Your Margins?

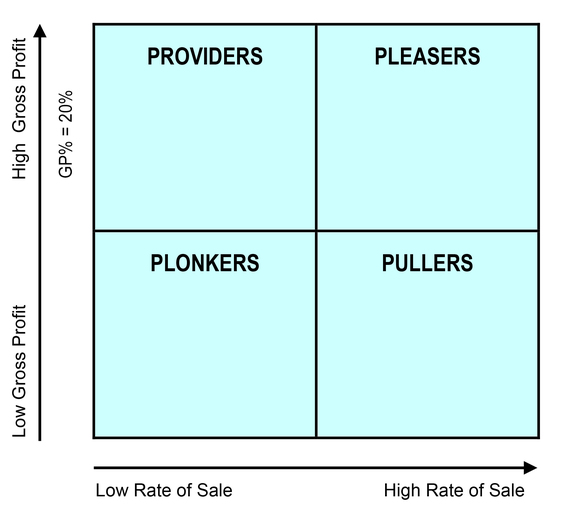

Here’s how Rx Management created a matrix of Pleasers, Pullers, Plonkers, and Providers to protect profits, drive up gross margins, and eliminate the money-losing duds in its business.

When Jim Harriott walks into one of Rx Management’s 18 retail pharmacies in Australia, he usually has four words for his managers: “Show me your plonkers.”

Plonkers are slow sellers with low gross margins. Once he sees them, Harriott will ask what the manager plans do with them. “The idea of having lines in the stores that aren’t selling is madness,” says Harriott, whose stores are about the size of a Walgreens in the U.S. “But that happens. We get all excited about the new lines that come into the store but we never get rid of them.”

Harriott has created a powerful matrix to keep these money-losing product lines out of his Sydney-based chain that is relevant to many industries. The matrix divides the products stocked in the pharmacies into four quadrants — pleasers, pullers, plonkers and providers — each with its own role in the ecosystem of a store. By providing a simple visual representation of how every product is performing, the matrix has helped the chain protect its margins from industrywide pressure for decades.

“It’s important that you don’t lose sight of the metrics that make a business successful,” says Harriott.

Waterfall Graphs

Stocking money-losing product lines isn’t a hazard unique to pharmacy businesses. As I discussed in my recent book Scaling Up, many companies hold onto money-losing product and service lines. “For strategic reasons” is usually the excuse.

Yet what is strategic about losing lots of money over a period of time? Apple could have easily argued that selling its money-losing handheld computers was a bad strategic move, but Steve Jobs eliminated the product line when he came back to run the firm a second time. Any loss leaders you might need — and these should be kept to a minimum — should be treated as a marketing expense in your accounting.

Having your accountant create waterfall graphs can force you to face the brutal facts about your own plonkers. Waterfall graphs are simple graphics that let you see gross margins or profit percentage by customer, location, sales people, product line or stock keeping units, usually called SKUs. The point is to have an easy way to see where the company is making a bunch of money from a limited part of the business and losing some in other parts. Harriott’s matrix is a creative application of this concept.

“When I saw the waterfall graphs, I said, “This is an opportunity to see things a little bit differently,” says Harriott. “It helps me make better decisions. That’s what the pleasers and pullers do for me.”

The power of simplification

Harriott started his first pharmacy in a small town in Australia in 1990. He sold that business in 2000 and then purchased a much larger urban pharmacy, followed by another. In 2011, he combined those pharmacies with others run by the company Rx Management to create his current operation. He and three other directors own the pharmacies and are franchisees of the company Priceline.

As Harriott scaled the business, he saw that it was hard for managers of the stores to keep an eye on which product lines were performing well. With 13,000 individual items — or SKUs — the task was overwhelming.

Harriott’s matrix simplified decision making for them by showing them exactly where each SKU falls in the four quadrants:

Providers: These are the lines that sell at a low rate but have a high gross profit. They are not price-sensitive. There are many items in this category, allowing the business to showcase the wide range of products it sells. (Top left)

Pleasers: These are star products that have great sales and great profits, such as popular skin care items and supplements. Pleasers have moderate price sensitivity. (Top right)

Plonkers: With a low sales rate and a low gross profit, these products have little going for them — and in most cases should be purged. (Bottom left)

Sometimes, new products that don’t have much sales history show up in this quadrant, in which case the managers remove them from the list. Other plonkers have the potential to become providers if a store raises their prices — which managers are encouraged to do.

But in many other cases, the plonkers should be dropped. The store may be stocking them because the manager fell in love with a product or is reluctant to disappoint a customer. Harriott often hears, “I know we haven’t sold many but Mrs. Jones comes in every three months and buys them.” In those cases, Harriott will suggest another approach, like special ordering the product for Mrs. Jones.

“You can’t have it sitting there not paying its rent,” says Harriott. “Each product has to pay its proportion of the rent.”

Pullers: These are popular, competitive lines that attract customers but are very price sensitive. “The pullers are the lines that you don’t make much money on but people buy a lot of,” says Harriott. One example is fish oil supplements which, as in the U.S., are a popular item in Australia. (Bottom right).

It’s hard to get stores to the point where they have no plonkers. Typically Harriott has found his stores will have 200 SKUs that are pleasers, 200 pullers, 6,000 providers and 6,000 plonkers. The managers must continually cull the plonkers, to keep the number down. And to prevent more duds from creeping into the stores, any manager who wants to add a new line is strongly encouraged to drop a plonker.

Higher Gross Profits

By doing an analysis of their stock each quarter, Harriott’s managers have been able to identify the products consumers really want and use that information to improve gross profits at their stores. All of the chain’s managers know to keep pleasers and pullers in stock at all time and root out plonkers.

“If you don’t have a compelling reason people should be coming to see you, some other provider will take the business from you,” he says.

The matrix also shows them which products to promote. If there are promotional opportunities in stores, managers know to allocate half to pleasers and half to pullers — and never to promote providers or plonkers.

One pharmacy manager has been able to increase her store’s gross profit by 1.5% to 2% over a 12-month period by concentrating on increasing the mix of pleasers in certain displays, says Harriott. “This ‘pleasers and pullers’ concept was key in growing the retail gross profit of the store from the 29% mark to the 30 to 31% mark,” he says. Most of this margin goes right to the bottom line.

Of course, keeping track of the products that fit into the four quadrants requires regular attention. But given that Harriott’s business faces pressure from big box retailers, it’s the best way to ensure the chain can hold onto its position in the industry. “Where we succeed in this is by managing our margins,” he says. If you are facing similar pressures in your industry, Harriott’s approach is an effective way to turn the tide and protect your margins, too.