40 under 40: Class of 2021

October 18, 2021The world’s best MBA programs for entrepreneurship in 2022

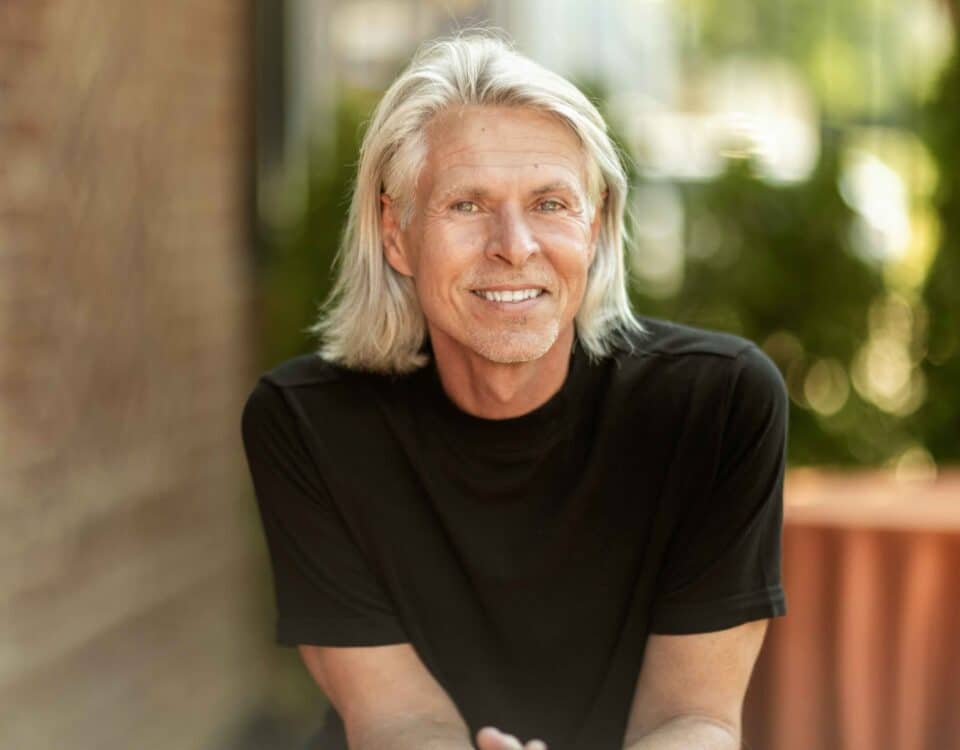

October 27, 2021By Verne Harnish

In the current labor market, many leaders of scale-ups are looking for more effective ways to engage and retain employees. Employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), now used by 6,500 companies, according to the National Center for Employee Ownership, are getting new attention, with leaders looking to create more equitable business models, as Sebastian Ross and I discuss in Scaling Up Compensation, the new book we co-authored.

StoneAge, a 160-person manufacturer in Durango, Colo., rolled out an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) in 2015. The company, founded in 1979, makes high-pressure water-blasting tools and automated equipment used in industrial cleaning. Currently, it brings in $55 million in annual revenue.

Building a stronger culture

One benefit of working for StoneAge is that all employees receive an annual ESOP contribution. Every year, the company gets a new valuation and releases company stock into all employees’ ESOP accounts; all of the shares are owned inside an ESOP trust.

In recent years, this form of compensation has averaged about 25% of wages, between new shares coming in and stock appreciation, according to CEO Kerry Siggins, a YPO member. “It’s a long-term benefit,” she says. “It’s a retirement account that grows much faster than a typical 401(k).”

With most of the company’s employees between their mid-30s and mid-50s, many understand the benefits of the ESOP to their retirement plans—but for younger recruits who are far from retirement age, the company has to invest more time in education. “Explaining it to a 25-year-old is not an easy thing to do,” Siggins says.

Beyond the ESOP, the company sets aside 10% of its profits and distributes it as a profit-sharing bonus to its employees at the end of each year—this year it will be about 15% of their wages. StoneAge also contributes to its employees’ 401(k) plans. “We believe employees need to be diversified,” says Siggins. The company also pays 100% of health insurance premiums for employees and 50% of their dependent’s insurance premiums.

Although there is a cost to benefits like these, Siggins says they are an important part of the culture. “We understand that these are long term benefits, and we need to attract and retain talent with our high performance, dynamic culture. We try to treat ourselves as a 42-year-old startup,” she says.

Understanding the tax benefits

One advantage to having an ESOP is tax benefits for both employees and the company. “The shareholder within the benefit plan does not have to pay income tax before they retire,” explains Siggins. “It’s a pretty significant tax deferral program for employees.”

At the same time, because the company is an S Corp, it does not pay corporate income tax. That is passed along to the shareholders.

The ESOP is not subject to income tax.

“The benefit of no distributions and not paying income tax means the company is generating a tremendous amount of cash,” says Siggins. “When you generate a tremendous amount of cash, you can reinvest in the company’s growth.”

Making compensation more sustainable

Before the ESOP, StoneAge ran an investment stock ownership plan, in which employees had been able to purchase shares of the company. They received quarterly dividends.

The company decided to replace this plan with an ESOP because the ESOP seemed more sustainable and equitable. “We didn’t want people to feel if they didn’t have money to invest or a risk appetite, they were somehow compensated less,” says Siggins.

Beyond this, not all employees were able to participate in the investment stock ownership plan, because the company is a sub-chapter S corporation and can’t have international shareholders. StoneAge has some international employees.

At the time the company switched to the ESOP, it decided to stop selling shares to employees through the investment stock ownership plan in 2014 and to stop paying dividends as of 2021.

Keeping employee retention rates high

Siggins says setting up the ESOP was complicated and costly—she estimates the tab was between a quarter and a half a million dollars. She recommends that companies planning an ESOP set aside nine months to a year to work with service providers, accountants and attorneys. Her recommendation is to work only with professionals who have experience with ESOPs, which are heavily regulated.

“There can’t be mistakes,” she says. “This is monitored by the Department of Labor and ERISA. There can be pretty significant penalties and potential for a lawsuit if it’s not done right.”

Although the investment of time and money was steep, Siggins believes that her company’s ESOP and other benefits have paid off, helping to reduce the impact of the labor shortage. Employees’ average tenure at the company is 6.8 years, and the company has more than 50 hires who have been with the company less than two years.

And when the company was targeted in a ransomware attack that shuttered all of its IT systems in 2020, employees went into overdrive to keep shipping to customers, tackling all of the work manually until the system was back up and running. Siggins believes they came through the hack stronger because of the commitment of its employee-owners.

“They care deeply about the company. The ESOP creates a tremendous amount of passion,” Siggins says. “People can walk away with hundreds of thousands of dollars if they stay with the company and keep it growing.”