Musk says first human has received Neuralink brain implant

January 31, 2024What I got wrong about loyalty at work

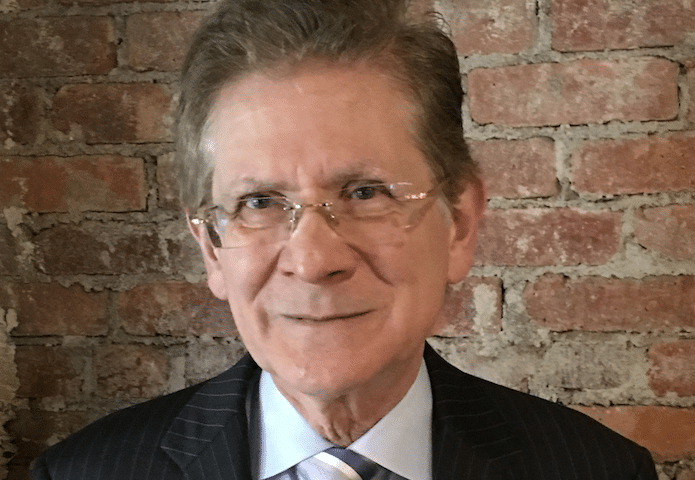

February 20, 2024By Verne Harnish

When Ron Tompkins joined 82nd Street Academics as executive director, he quickly positioned the New York City-based nonprofit for growth. The organization helps students prepare for higher education, serving young people who speak Bengali, Mandarin, Spanish and Tibetan at home. Designed to complement public education, it offers services such as after-school homework help, an eight-week summer program called Summer Learning Gold to help students start the school year with a solid foundation in math and English, and preschool programs.

However, even in a nonprofit that’s careful about spending, growth sucks cash. After 82nd Street Academics borrowed money to expand into a new facility in Jamaica, Queens, the cost of rehabbing the aging building to code put the organization’s budget under massive pressure.

Leaving payroll crises behind

It was hard to make payroll, given the organization’s 158-person team at the time. With just $13,000 in the bank and the next payroll looming, Tompkins and three other members of his leadership team attended a Scaling Up workshop in 2015 to seek ideas. After that meeting, they successfully obtained emergency loans with the help of their board, reduced the nonprofit’s administrative costs to 15% of revenue and sold the building in Jamaica.

Along the way, Tompkins became certified as a Scaling Up coach, opening his practice in 2016. He is leaving 82nd Street Academics to go full-time in his coaching practice in March 2024, where he will continue serving nonprofits and other clients.

By the time Tomkpins went full-time, the agency had grown to five campuses and partnered with the Department of Education in Queens, N.Y. to create two sites for Universal Pre-K programs. It also diversified its funding with $3 million from government agencies. Outside of work, Tompkins and his former spouse raised 11 foster children during the time he was pursuing his nonprofit career.

Today, Tompkins, based in New York City, is drawing on what he learned to coach clients in the nonprofit space. Here is a look at how he helped turn around the organization using the principles of Scaling Up and position it for the future.

Streamlining middle management

Making payroll is a perennial challenge in the nonprofit sector, where many organizations are heavily dependent on donations and grants. One critical change Tompkins implemented was paring down middle management. For instance, the nonprofit eliminated an associate director’s position, relying on the senior team and other employees to get things done. “People are a lot smarter than you think they are,” says Tompkins.

Prioritizing intellectual property

82nd Street Academics embraced a set of developmental tools called the 5 Forces to help children prepare for college, taking steps to document this valuable intellectual property. Among the population it serves, 75% of the young people are not English speakers at home. In Jackson Heights, Queens, the part of New York City where the nonprofit is based, a student has about an 18% chance of graduating, with a BA. Despite these challenges, the organization was achieving consistently impressive results.

Validating a successful methodology

During Tompkins’ tenure, 82nd Street Academics increased enrollment from 300 to 1,200 students, and increased college attendance among the students by 40%.

To validate the success of its 5 Forces program and support its funding requests, the organization retained a data clearinghouse to track its progress in achieving key metrics. “We’re coming up with leading and lagging indicators for short-term evidence of our intellectual property,” says Tompkins.

Avoiding the “The Valley of Death”

Many businesses find themselves in the “Valley of Death” as they scale if they are not careful, burning through cash at a faster rate than they can sustain as they invest in growth. The same can hold true for nonprofits, as Tompkins learned, particularly as they grow to $1 million to $6 million in annual receipts. “What might be a common cold to a for-profit is pneumonia for us,” says Tompkins.

Although the organization had taken out loans to pay for the rehabilitation of the new building in Jamaica, Queens, the preschool was not attracting enough students to be sustainable financially because of demographic changes in the area. Many Bengali families were moving into the area, and their cultural belief was that four-year-olds were not old enough to go to school. “We ran it for two or three years but could not get the numbers to make it sustainable—and in 2015, we were suddenly out of cash,” says Tompkins. “With payroll coming, that’s very scary.”

Ultimately, it made sense to close down the building in Jamaica and write off the loss of money invested in rehabbing it. “We could not afford programs that could not at least hold their own for direct expenses,” he says. Making that tough decision with the board’s support that made the whole enterprise more sustainable.

Tompkins is transitioning out of his role at the organization as he embraces full-time life as a coach, but he has left it with a powerful legacy. At one meeting with a funding agency, an administrator pointed out that 95% of nonprofits want to do work that’s “on the easy end of the log.” He said the agency was looking for those willing to work on “the heavy end of the log.”

“That’s our mission,” says Tompkins, who is confident that the team he built will continue tackling the tough educational work few in the nonprofit sector feel confident taking on.